1/(Effective Altruism)

Why discounting for distance and time may be the better way to go

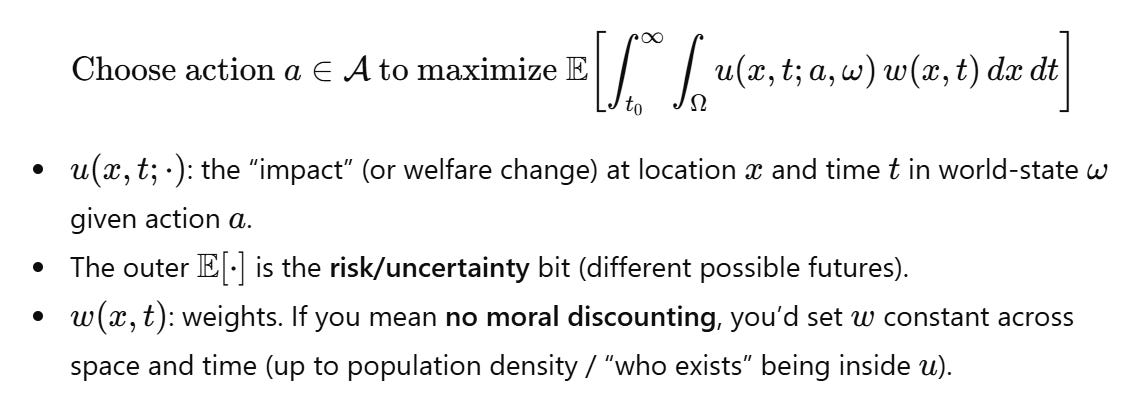

I am sure that I risk oversimplifying or mischaracterizing the movement, but a useful summary of Effective Altruism might be to “give charitably in the way that maximizes positive impact”. Furthermore, most EA proponents argue something like “Give in a way that maximizes positive impact equally over all space and time.”

In other words, a key component of the whole thing is to not “discount” impact for distance or time from the recipient(s). People far away, or in the distant future, are just as valuable as those nearby and in the now. But does this really make sense?

To poke at the idea, consider its reciprocal instead (hence the title of this essay)… the idea of maximizing the positive impact of your charity on others that are nearest to you in space and time. AKA “Take care of the people closest to you first.” Might this actually work better?

Maybe one of the reasons that EA gets a lot of pretty emotional criticism (outside of Sam Bankman-Fried) is that the idea of not discounting for space and time only makes sense in the case where YOU are the only person in the whole world able to be charitable - an offensively arrogant and self-centered perspective. If you instead imagine that there are lots of other capable people just like you making the same choices about what to do, the optimal outcome changes. When you are playing on a team, the best strategies are different then when you are playing alone. If everyone is doing the same thing (or even just lots of other people), consider that you will be able to much more accurately measure the impact of your giving on those closest to you. Considering your nearest neighbors reduces uncertainty and therefore increases impact. Assuming that you are pretty similar to others, the optimal global outcome is for you to help the people closest to you.

In fact, this idea of discounting by distance as a way to create an optimal outcome shows up in other places as well. Adam Smith’s “Theory of Moral Sentiments” (a favorite of mine) was the often-forgotten prequel to “The Wealth of Nations”. In it, Smith suggests that the reason the “invisible hand” (the actions of a dispassionate market) actually works is because people tend to look after those nearest to them. A moral compass, applied mostly locally, is in fact the underlying requirement for stable markets. This is unintuitive and indeed the opposite of what most people believe: that markets give rise to stability due to self-interested ‘rational actors’. In reality, irrationality (loving your friends more) is a requirement, and a good thing.

A similar preference for one’s nearest neighbors is found in the ‘flocking’ rules that give rise to the magnificent emergent beauty and complexity seen in murmurations. In the flock, birds consider only the movements of nearby neighbors (a recent paper suggests as few as 7 neighbors), and in doing so optimize for their survival and energy expenditure.

In a recent podcast conversation with philosopher David Edmonds, Sam Harris talks about the unfortunate fact that we tend to experience the description of a single person’s death as having more impact than hearing about a faraway disaster in which many have died. But might this be a feature, not a bug? Perhaps the emergent effect of all of us doing this at the same time actually improves overall collective welfare. While there are certainly some very negative consequences one can imagine, such as rich people giving to their children when they could be giving to needier and less-related people instead, the overall impact might still be optimal.

As Harris mentions in his podcast as well, the most important thing is that we all need to give more, regardless of strategy. So consider this whole conversation as a hopefully enjoyable digression on a second-order concern. If you got anything out of this, please just give more.

Let me close with a spiritual aphorism which is entirely orthogonal to this conversation… “Charity is for the giver.” Beyond all considerations of utility, we do not give enough, and when we do give, it enriches one’s self most of all.

A study by the Center for Effective Philanthropy on the grants given by MacKenzie Scott shows some evidence that unrestricted funding enabled transformational impact for some of the organisations. The thing that most directly impacted outcomes wasn’t just the funding in itself but that the availability of funding created a cultural and psychological confidence that enabled teams to pursue bigger objectives.

Philip,

I agree with you on discounting time. Treating future impact as fully equivalent to present impact often becomes an excuse for abstraction, moral outsourcing, and of course focusing on hypothetical future problems to avoid the here and now real problems – what I see as morally wrong in longtermism.

I am less convinced about discounting distance. Birds operate with simple local rules in a tightly coupled physical system. Human societies are layered, symbolic, political, and technologically entangled. Local actions routinely have non-local consequences, and what looks like “distance” is often the artifact of ignorance, mediation, or cultural framing rather than a real separation of effects. Supply chains, financial systems, climate, conflict, and information flows collapse distance whether we like it or not.

On charity being “for the giver,” I agree in the existential sense, but my experience with humanitarian NGOs (NGOs being the common vehicle for individual remote “giving”) and state actors complicates that framing. The gap between state actors and NGOs is staggering, not morally but structurally. NGOs are agile, visible, emotionally legible, and politically convenient. States are slow, opaque, and routinely hypocritical. Yet in terms of raw effectiveness, capacity, and causal power, states operate orders of magnitude above even the largest and well managed humanitarian NGOs.

The problem is that the same state entities that fund humanitarian relief are usually the ones funding the wars or the creators of the problems that make that relief necessary. I agree that the moral focus on the nearby should begin with individuals, but it cannot stop there. We are the state - unless we really want to undo two thousand years of res-publican or democratic thinking, hence my usual questions to Americans asking which part of “We the people” are they? And in a res-publica and a democracy our individual and local moral impulses MUST coalesce into our collective institutions to become the action of the state. If that fails, then we all have failed. We deserve the leaders we elect.

And when states are forced to act and are evaluated through an altruistic lens shaped from the bottom up, they are also forced to confront the asymmetry between how efficiently they organize harm and how unwilling they are to apply the same effectiveness to preventing it. After my 35 years of UN, I see this asymmetry as staggering, and the underlying reason why the nations are not “united” anymore – this hypocrisy has been brutally exposed, and many of the 195+ nations comprising the UN are not anymore willing to follow the lead of the ones that founded it some 80 years ago – the legitimacy once had is long gone.

At the UN we used to say that the tiny fraction states devote to humanitarian aid compared to military spending functions largely as conscience-washing, and I would argue that the same applies to a lot of EA funding. But if the same states were simply to reduce military expenditure on those wars, they would alleviate vastly more suffering than decades of downstream humanitarian aid ever could.

My 2 cents...