The Linden Dollar is the digital currency of Second Life, which has been used by millions of people over the last 20 years to trade around $10 Billion in virtual goods and services. It has maintained a stable exchange rate against real-world currencies through a unique set of policies including a basic income. It came into existence six years before Bitcoin, and provides real-life jobs for thousands of people. As a digital currency in a virtual world, it has provided a unique opportunity to learn about how economies work (and sometimes how they don’t work). I thought I’d write down a history of some of the fun that I could remember here, in preparation for a talk I’m giving at the Consensus conference.

Medium of Exchange

This very early picture from the earliest days of Second Life shows a makeshift bazaar where the typically hilly land was lowered and flattened, and people brought things they had made to a common area to sell to each other. What you can’t see in the image is that many items in Second Life are ‘self-vending’ - meaning you can click on the object and buy a copy for yourself.

Unlike a typical video game, where you navigate some constraints to reach a goal, Second Life is an open sandbox world where you can build almost anything, together with millions of other people. There is a set of building block shapes (called ‘primitives’) and a programming language letting you make anything - from a pair of sunglasses for your avatar, to a piece of furniture, to a motorcycle you can ride around with a friend on the back.

The whole point was to build things with other people, and right away people built things… millions of different things. And so naturally there was a desire to trade, and with it the classic ‘coincidence of wants’ challenge that creates a need for a currency: If you make ornate victorian lawn furniture and fall in love with a pet kitten made by someone halfway across the virtual world, you’ll need some sort of way to pay for it without direct barter.

So this was the fundamental purpose of the Linden Dollar (or L$ for short). We built in a digital currency that you could use to trade things easily. Each person had a balance of these digital tokens (more on how you came to have them later), and could use them either to pay another person directly, to buy their own copy of an interesting thing they found in the world, or to pay money to an object (like a vending machine or tip jar).

Stipends: Priming the Pump with Basic Income

But how to create a circulating supply of currency from the start? In the beginning, there were only a few hundred people making strange virtual things with no immediately obvious value to each other. And so the idea of selling them units of currency that they might or might not someday use to trade things seemed crazy, even by our standards. But we knew that we needed to get the currency circulating to be useful, so instead we decided to give a weekly free allocation to everyone to get things started. And that is still part of the monetary policy to this day - printing and giving a weekly stipend of linden dollars to a large number of people - although now we can do this only for the subset of people for whom we have unique identity information.

If this sounds like the ‘Universal Basic Income’ that is being debated and considered by governments, it is! Second Life has been an interesting experiment in directly giving equal units of a currency to a lot of people. Millions of dollars a year (USD-equivalent) are given out in these stipends, to hundreds of thousands of people. These direct payments are something like one percent of the overall economy, and less than one tenth of the money taken out of the economy by people exchanging their L$ back to USD (or Euros). As far as we’ve been able to tell, and in agreement with the many other UBI studies made in the real world, giving everyone a small regular supply of money seems to effectively stimulate the economy. Obviously in the real world the impact of UBI is potentially much larger - people in Second Life weren’t suddenly able to afford healthcare for their kids, for example - but a basic income seems to have the same general positive effect.

Sources and Sinks, without a Federal Reserve

Crypto is simple in that there is either a fixed number of tokens in circulation, or an a-priori algorithm which determines production and deletion of tokens. But of course this causes the price to vary dramatically with the demand for the token, making it unsuitable for use as a currency. In our case, because we needed a medium of exchange with a stable price, we had to build some sort of mechanism to adjust up or down the amount of money in circulation to match the population and productivity. But of course we also didn’t want to create an opaque system that would create distrust and the risk that we might start wildly printing currency like a corrupt government.

What we did instead worked really well, managing to keep the open market exchange price of the L$ stable to within a few percent over the past 20 years, without maintaining reserves. Here’s how we did it:

Sources:

We create new L$ in two ways. The first, which I already mentioned, is stipends - giving a weekly amount of new currency to each of hundreds of thousands of people. The second was open-market sales of new currency. To do this, we gave the guidance to Second Life residents that a person in the finance department would use their own best judgement to mint and sell at market price new blocks of currency, with the goal of keeping the exchange rate constant. The sale of these blocks of currency were made transparent to the public, along with the overall money supply and other statistics about the economy.

Sinks:

A number of different actions in Second Life remove L$ from the economy (in crypto this is often called ‘burning’), typically as small fees for things that have an operational cost to the company, such as uploading images or creating groups. In this way, the money supply was gradually reduced.

Tax Revolts and Tea Parties

At the start of 2003, before Second Life had officially launched, we designed a sort of ‘improved property tax’ system with the goal of better balancing the use of system resources amongst residents. The idea was to automatically levy a weekly tax (in L$) based on the number and details of virtual primitives residents had placed on property they owned. The problem was that it was easy to make complex objects that might overwhelm the graphics and simulation power of the system, leaving less available resources for your neighbors. Things like the size of objects, whether they had lights, whether they could move, and other factors all were included in the calculation of the tax. The problem was that is was very hard to estimate what the tax cost of something you were building might be… sort of like the problem of estimating your taxes in the US, but there I digress.

The result was both comical and a great learning experience. Residents led a tax revolt complete with a Boston Tea Party event, and we ultimately gave in to the pressure turned the confusing tax system off. I couldn’t find any pictures online, but I know there are some funny ones out there.

In retrospect, I wish we had re-designed the system to be easy-to-understand, because I think it would have more fairly allocated resources and might have even been fun to work within the restrictions/fees imposed. What we were left with was more of an honor system, where residents have to complain at their neighbors to manage their use of blinky lights or exploding toys. But honestly I’m still not sure - this is a good example of how complex the design of systems of governance can be.

Monopolistic Landowners and Ad Farms

Recent crypto virtual world projects like Decentraland often wax eloquent about how ownership of virtual real-estate confers ‘uncensorable immutability’ via the blockchain. And, in the early days of Second Life, that was pretty much what the rules were as well - land owners could do anything they wanted to with land. The world was one huge contiguous landscape, with parcels that could be subdivided in any way you wanted down to tiny 4x4 meter plots. And of course you could build whatever you wanted on those plots - as high into the sky as you liked, for example.

But owning property in this way confer a monopolistic and unfair advantage to the owner. Since your neighbors have no power of your actions, you can exort them by setting a huge price on a tiny parcel in a busy neighborhood, playing loud music, putting up big ugly walls with ads or pictures, etc. Without governance rules around zoning and land use to balance an open property market, profit-seeking landowners would overpower their neighbors.

This imbalance was corrected in two different ways. One was that neighbors banded together and established co-ownership of large continguous properties, with local rules as to property use and development, in a manner similar to co-ops, gated communities, or condo associations. A second way was global company policy on the use of land for advertising or extortion. You can read the details of the company policy on using land in this way here.

Tip Jars and other kinds of Micropayments

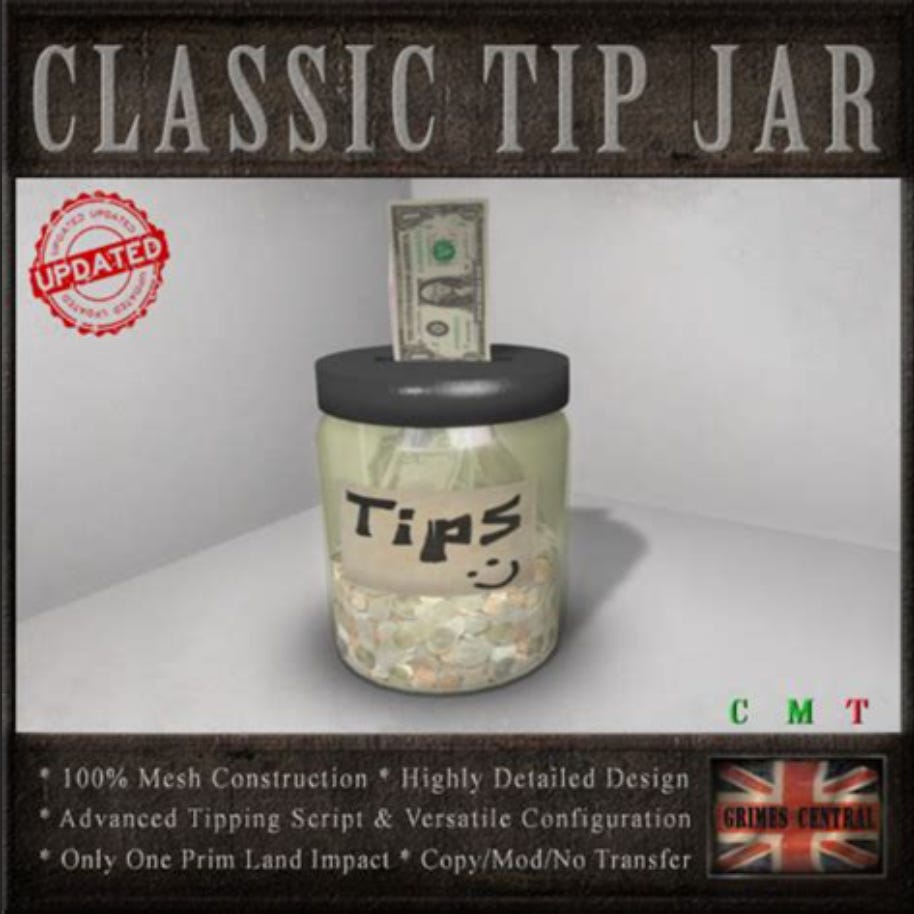

There are no fees for paying even a very small amount of money in Second Life. Unlike crypto or credit cards, transaction fees are zero. This opened up a lot of fun options to pay small amounts of money for things, and drives a lot of the economy: the average transaction size in Second Life is around one dollar.

If you listen to live music or a DJ in SL, there will likely be a tip jar. Because it only takes you a couple seconds (and no need to sort through your wallet for change) to click on it and pay someone without needing to walk over to the jar, you are much more likely to do it than IRL. Additionally, scripts attached to the jars make it fun to add features like celebrating or otherwise announcing the avatar who left the tip, etc.

The success of these small transactions creates a lot of income for people in SL, and I wonder whether micropayments might not improve things like journalism in the real world. I’d much rather directly pay $0.10 to read an article than pay the New York Times $7/month for a bundled subscription where I can’t specify the writer I’d like to compensate. It is sad that with all the energy spent on crypto, we still don’t have micropayments working broadly.

Bitcoins bought at virtual ATMs

As a fascinating sidenote, many people bought their first bitcoins in Second Life ATMs, an easier alternative to setting up a PC and becoming a miner in the years before the existence of widely used cryptocurrency exchanges. There were vending machines from a company called VirWoX early in 2011 that allowed conversion of L$ into BTC. As far as I can tell, there were bitcoin ATMs in Second Life before such ATMs existed in the real world!

Of Ponzi Schemes and Wildcat Banks

From 1836 to 1865, wildcat banks in the United States could offer printed bills with little or no regulation as to redeemability or deposit requirements. You can imagine what sort of shenanigans ensued. Similarly, the fact that you could deposit L$ into an object (vending machine, tip jar, etc) meant that in the early days many different get-rich-quick schemes also appeared in Second Life that we as a company had to address with governance and policy.

One particularly notable one was a ‘bank’ called Ginko Financial offering exceedingly high rates of return (60% annually) on deposits. As you might imagine, withdrawal of funds eventually became… difficult. An AlphaVille Herald article here has long and humourous investigative journalism conversation with the proprietors.

As you might imagine, we decided soon after to restrict things-that-looked-like-banking-activities to those provided by actual banks. Lots of parallels here to the innumerable rug-pull adventures of the more modern crypto ‘De-Fi’ segment. And if you haven’t laughed out loud reading about some of those, may I please introduce you to one of my favorite writers and thinkers, Molly White.

Implications for the Real World?

Second Life has been a fascinating and ongoing experiment in creating a world with alternate rules. Some takeaways:

It seems possible that a community could print its own currency with a stable value without a reserve, provided it agrees to create and sell things of value (as Second Life residents do) in that currency. This is what my new project FairShare is all about - if you are interested in working on it reach out.

Striking a balance between centralization and decentralization (instead of going all the way to communism on the one hand or web3 on the other) seems to be important to a harmonious and broadly compelling experience. Moreover, I suspect that doing this ‘bottom up’ by allowing people to form nested groups with shared rules and norms is the way to introduce this structure, rather than top-down by government. Many of the top-down things we had to do hastily to keep Second Life alive (like zoning rules or moderation standards) could be done bottom-up through groups.

Transparency is a tool than can sometimes do things that you might otherwise achieve with decentralization, but at a higher cost. For example, publishing the money supply and currency sales allowed us to be better trusted than a central bank, without needing to build decentralized blockchains to restrict the amount of currency in circulation.

Transaction fees are a regressive tax that negatively impacts the earning potential of people selling less expensive things. Eliminating them with real-world micropayments both on and off-line might increase the real-world economy more than we might think.

In any diverse, interesting world that you might want to live in, one person’s Utopia is bound to be another person’s Dystopia. So instead of trying to find one rule that fits everyone, focus on empowering local communities and groups with the ability to change the rules to their own satisfaction. This seems like a hopeful direction for both virtual worlds and, more broadly, social media.

What an excellent read. I remember the prim tax days well and the absolute horror to learn I'd left a single cube floating somewhere hundreds of feet up in the air that cost me L$1000.

According to Noam Chomsky there's little or no difference between the Democrats and the Republicans.. see 1988 interview with Bill moyers... They're all crooks.. and Chomsky has some major credentials for his comments considered by some to be the leading intellect of the 20th century and his work with linguistics is/ was formidable.. I would think that his point of view on this would be the matter of trust the populace has in the leadership... pretty much on the floor.. and Joe and Kamela have the distinction of out racing even Trump... Who in retrospect is turned out to be pretty accurate in some of his accusations and predictions... Robert