Beyond Dunbar

Tech can build trust and enable stronger local communities

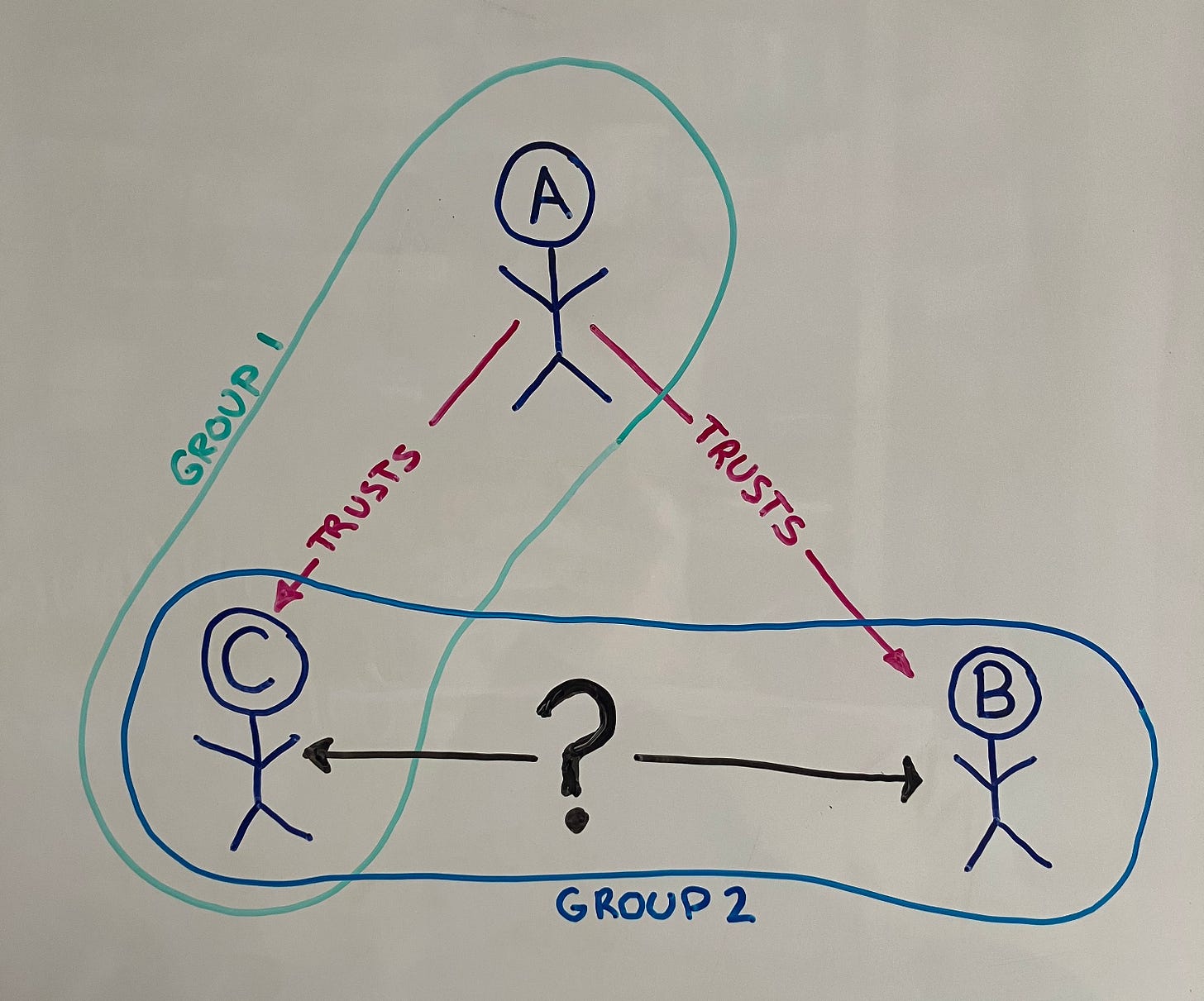

Imagine person C and person B are chatting in a cafe, never having met each other before. Could we quickly help them to begin to trust each other? It is likely that they may have a friend in common (A) or a shared group affiliation (2) that they are not aware of.

Our greatest achievements have come from working together. The ceaseless action of living things is to build structures larger and longer lasting than ourselves. Many of these structures are built by groups of us, working together. But to succeed in such collaboration, we often must establish trust with each other.

The Dunbar number was coined by anthropologist Robin Dunbar, and refers to the largest number of people (around 150) with which the average person can have a strong bond of understanding and trust - remembering both the details of their own relationship with each person, as well as how the others relate to each other. The limit is set by the finite capacity and memory of the human brain: If we had bigger brains with more neurons, the number of people we could know well would be larger.

The earliest human societies seem to have been self-sufficient groups of around this size, and many examples of the number can be found in things like team sizes in companies, military units, village populations, or church groups. More people can survive better by cooperating than fewer, but beyond the Dunbar limit, inter-personal trust and cooperation breaks down and coherence drops. Beyond a point, we must fall back to using money or violence to negotiate interaction.

Can tech help? Sadly, a lot of recent work in tech has gone in the opposite direction - actively damaging the delicate bonds or friendship and group affiliations that enable trust. For example, social media sites like Twitter are organized to strip away knowledge of affiliations in exchange for polarizing debate around a single topic or post: You can easily find yourself hurling insults about political parties at your doctor or co-workers or high-school friends. To rise above the ever-growing noise of online activity, these sites try to reduce us to an anonymous, naked, friendless, outraged opinion. Another way of looking at it is that big companies are actively replacing our closest bonds with themselves: rather than relying on neighbors to borrow tools from or hear news, we rely on Amazon and Twitter instead.

But we can just as easily use tech to increase the strengths of these bonds.

Friends-in-Common: Six Degrees

As Kevin Bacon made famous, we are all better-connected to each other than we think. Humans can easily recognize and remember about 1,500 other people. If each of those people knows 1,500 people of their own, that means that even in a city of 2 Million people everyone else is likely known personally by someone you know. And if you are willing to meet some new friends that are friends of your friend’s friends… you could have as many as 3.3 Billion people to choose from! This is why, for example, you often have shared connection with others on LinkedIn.

An app that could instantly tell you that you have common friends with someone you just met or even just someone you knew was nearby would be… wonderful! And - if you are worried about risks to your privacy - such an app can be built that stores all it’s information completely on your own phone and never communicates with any centralized servers. There is no need to risk any private information to discover you have friends in common.

Imagine going into a party or conference, and being able to see that there were five other people there with whom you shared a friend-in-common. And you could send a message to those other people, if you wanted, asking them if they’d like to meet up. This would not risk your privacy - if you received such a message from someone else and didn’t choose to answer, there would be absolutely no way for them to find you (see section on location sharing below).

Nested Groups

Group affiliations are the other thing that strangers often share that can help build trust. Some common ones we often talk about are the High School or College we attended, companies where we worked in the past, particular skills we have (like being a pilot, programming in a certain language, playing a musical instrument), places we have been (vacation spots, restaurants, cities, mountaintops), or even secret societies to which we might belong.

These affiliations can be hardened (so that people can’t fake having them to stalk or troll each other) by creating online groups with control over their membership. You can imagine, for example, an ‘official’ alumni group for a university that only lets you into the group if you really did go there. If the members in the group have actively vetted that another member is an alumnus, they very probably are. Another example might be a group like “New York City Residents” that actively checks and requires proof that you really do live in the city.

More broadly, group membership can also be controlled by simple democratic governance tools: you have to get voted into the group, and you can be voted out. This enables useful, more abstract groups like “Friendly, Optimistic, Software Entrepreneurs”. The group wants to maintain its reputation, and will therefore manage its membership appropriately. And the longer the group has existed, the more serious and valuable its ‘brand’ will become.

Finally, imagine that groups can be members of other groups… nested inside each other. So “Friendly, Optimistic, Software Entrepreneurs” could have regional groups (maybe to facilitate face-to-face meetups) as well as a larger global group that votes in the regional groups. Or, “Friendly, Optimistic, Software Engineers” could be voted into the larger, more general group “Software Engineers”. If a sub-group is behaving badly, the parent group can vote that group out by calling for a vote of the other sub-groups. Nesting groups creates much larger groups - meaning a greater likelihood of strangers being connected by one or more. A simple application of nested groups would be, for example, Boise→Idaho→USA as a way of safely and privately identifying citizens of nation-states, relying on the most local groups to be the ones actually checking the IDs… similar to how we do voting in the United States: If the ‘Idaho’ group lets in cities having appropriately validated their memberships, and the ‘USA’ group does the same for states, two people could identify themselves to each other as US Citizens without needing to show each other any further personal information. Trusting sub-groups to maintain accurate membership means that you gain the freedom to protect your own information from surveillance… this is an important example of why trust between individuals at the local scale is needed to avoid the risk of delegating trust to too large a state actor.

Two people meeting for the first time will likely share many group affiliations, if these groups were made digital, nestable, and democratic-where-appropriate, as described. Imagine how enjoyable it could be to make these connections as a part of meeting a new person. As a security sidenote, remember that people do not need to disclose groups to each other of which they are not both members. This type of system can be built with complete privacy - you cannot know someone else is in a group unless either they choose to show you, or you yourself are in that same group.

Group memberships can also be used to allow safe access to events or locations. For example, I could have a political town hall event where a large number of local groups were allowed to attend, provided that they agreed to manage the behavior of their member attendees. This would protect privacy (proving that you are a member of a group does not disclose your actual identity), and would also curtail extreme behavior (your group will sanction you if you are observed by other group members to have violated the standards of behavior agreed to by the group for the event).

Sharing Locations

For your closest group - for your ‘chosen family’ - you might already be sharing location information with some or all of them. Knowing where a close friend is has become a popular and positive example of trusting and giving trust to others. But the popular existing location services are generally either platform-specific (iOS), or part of broader insecure surveillance-based social media platforms (SnapChat, Google Maps).

But, as with divulging friends in common, E2EE (end-to-end encryption) can be used here to allow individuals or groups to share their locations with each other completely securely - no one other than the friends you choose can know where you are.

For cases where you just want to know friends are nearby but don’t want to see (or share) your precise location, the same secure technique discussed with friends-in-common can give a safer approximate answer. Imagine, for example, travelling to a faraway city and being able to see a sort of ‘heat map’ that showed you roughly that there were other members of a group (say an alumni group from a place you used to work) in the same city. And knowing that if you really needed it, you could send a message to everyone in that same group and see if anyone was available to meet up and help you.

Summary

With today’s tech and the pervasiveness of smartphones, it is very possible to build an app that lets you instantly find friends and groups in common with other people, without any risk of privacy breach or surveillance. Combining this with location services would make it easy to find people you can trust, wherever you may go. This seems like a sensible thing to build that would be of service to us all.

This concept is built on what you are writing about, and btw inspired by your LoveMachine. :)

https://hackernoon.com/karma-love-on-the-blockchain-and-the-gamification-of-helping-others

Would there still be a potential to use groups in a negative context (use as a blacklist to exclude individuals)? Is this good or bad in your opinion? I do like how VRChat implemented self forming/moderating groups, with ability for people to see and join groups based on being a member or friend of member, etc.